Art Periods – The Different Art Movements at a Glance

This post may contain affiliate links. We may earn a small commission from purchases made through them, at no additional cost to you.

Art has been created by humans for as long as we have been on this planet. As time has progressed, various art periods have taken shape and evolved into new ones. Understanding your art history timeline is important for anyone wanting to really appreciate the significance of artworks and why certain ones are so famous. Below we will unpack the art movements timeline, exploring the many different styles that have come about over the course of history.

Table of Contents

- 1 When Do Eras of Art Begin?

- 2 Art Periods at a Glance

- 3 Art History Timeline

- 4 Romanesque: Paintings as Reading Material

- 5 Gothic: Higher, Further, Freer – With Decline in Sight

- 6 Renaissance: Rebirth of an “Era” That Never Existed

- 7 Mannerism: A Brief Period of Kitsch

- 8 Baroque: Glorification of Power & Optical Illusions

- 9 The Rococo: A Comedy of Light, Air, and Colors

- 10 Classicism: Forward – Back to the Future!

- 11 Romanticism: After Severity, a Surge of Emotion

- 12 Realism: Reality Over Beauty

- 13 Impressionism: The Old World Ends, a New One Begins

- 14 Symbolism: Bitter Enjoyment of Sin, Death, and Passion

- 15 Art Nouveau: A Kiss Travels Around the World

- 16 Expressionism: Painting as Social Criticism

- 17 Cubism: Piecing the World Back Together!

- 18 Futurism: Classical and Hostile to the Body

- 19 Dadaism: Nonsense as the True Meaning of Things

- 20 Surrealism: Everything Real is Really Unreal

- 21 The New Objectivity: Focus on Pure Functionality

- 22 Abstract Expressionism: Art Emigrates

- 23 Pop-Art: Everything is Art – Art is Everything

- 24 Modern Art in the Art Movement Timeline

When Do Eras of Art Begin?

Ever since man has been aware of himself as a human being, painting has been around. The oldest preserved drawings and paintings of mankind, mostly in caves and under rock overhangs, were created in the younger Paleolithic Age and are thus up to about 40,000 years old. This is fairly well confirmed by measurements with the radiocarbon method. Friedrich Schiller answered the question of why people paint in his own way: “Man paints himself in his gods.” What seems comprehensible at first glance, however, does not really answer the question on closer inspection.

It is striking that especially the depictions of animals in many cave paintings are often more vivid and realistic than those of painters of later times. Which brings up the question: Why did artists from different eras paint so differently? In the following article, we would like to give you an overview of these art periods and their characteristics.

By the way: Have you ever noticed that the ‘official’ art periods only begin with the Romanesque period, as if there had been no painting before? But there was, as we have shown above, and of course, people have always painted between the Stone Age and the Romanesque period. We have wonderful pictorial evidence of the Romans and Greeks of antiquity, but several thousand years before them, wall paintings were created in ancient Egypt, and in Crete, fresco painting developed around 2000 BC, which left behind amazingly naturalistic portraits.

The fact that we do not divide these artistic works into eras is due, among other things, to the fact that they were each created in a more or less limited space, while almost all of the so-called art periods of today span several countries, often the entire European continent, and sometimes North and occasionally South America.

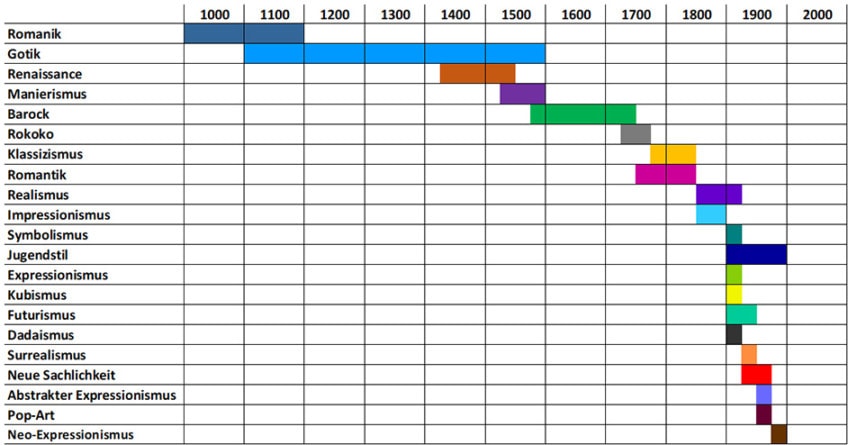

Art Periods at a Glance

The numbers in brackets should always be taken as an approximate frame because depending on the country, the respective period began or ended sooner or later. Nevertheless, the data below provides you with a framework for tracing the development of art. If you look closely, you will see that the individual periods often overlap considerably in time. Some art movements, especially in more recent times, even coexist.

- Romanesque (approx. 1000 – 13th century AD)

- Gothic (approx. 12th – 16th century)

- Renaissance (around 1420 in Florence – approx. 1520)

- Mannerism (ca. 1520 – ca. 1600, in Italy partly even later)

- Baroque (end of the 16th century – around 1760)

- Rococo (ca. 1725 – 1780)

- Classicism (ca. 1770 – 1840)

- Romanticism (approx. end of 18th – middle of 19th century)

- Realism (approx. middle 19th century – approx. 1925)

- Impressionism (ca. second half of the 19th century – ca. end of 19th century)

- Symbolism (ca. end of 19th century – ca. 1920)

- Art Nouveau (approx. end of 19th century – beginning of 20th century)

- Expressionism (approx. end of 19. century – approx. 1914)

- Cubism (ca. 1906 in France – ca. 1914)

- Futurism (from 1909 in Italy – partly until 1945)

- Dadaism (1912 – ca. 1920)

- Surrealism (ca. 1920 – ca. 1930)

- New Objectivity (ca. 1925 – mid-1960s)

- Abstract Expressionism/Tachism (late 1940-ies – early 1960-ies)

- Pop Art (in the mid-1950s simultaneously in Great Britain and the USA – end of the 1960s)

- Neo-Expressionism (from 1980 – 1989)

In the case of the art styles that have appeared since then and are becoming more and more “small-scale”, one does not usually speak of art eras anymore. Although, this term has been inadequately applied to most art movements since the end of the 19th century at the latest. Some people already spoke of the “end of painting” several decades ago, whereby you can see even at a superficial glance how nonsensical this is. Man continues to paint cheerfully, as in the Stone Age, without being classified in any kind of drawer or so-called period.

Art History Timeline

We have clearly presented an art movements timeline for you. From 1000 A.D., through the art styles of the Middle Ages to the modern art movements of today, you can classify the individual art styles in the overview of periods.

Romanesque: Paintings as Reading Material

(1000 – 1300)

When looking at an art periods timeline, this is generally considered the starting point. Romanesque painting began sometime around 1000 A.D. in direct connection with the increasingly powerful Christianity. Very few people were able to read at that time, so there should have been another means to teach them what they should believe, apart from the service. Romanesque painting consists almost exclusively of Christian/ ecclesiastical objects and images of people who played a role in the church, for example, the saints. In addition, there were the secular and especially the church dignitaries, which was often the same.

It is often said that the Romanesque images were there for the simple people to “read”. This means that they had to be kept simple. Romanesque paintings, whether in book painting, wall painting, panel painting, or as mosaics (which has nothing directly to do with painting), therefore usually have firm contours and relatively simple areas of color. There is no depth of space (perspective), and hardly any “natural” images.

Surely you have already noticed that in Romanesque paintings, different people are depicted in different sizes. This tells you that the person painted in large size is more important, more significant, than a small person next to them. In addition, you may have noticed the often strange contents of such paintings, up to and including frightening dragons.

Romanesque paintings have a high symbolic content. Human faces are often dramatically distorted. These paintings often tell highly emotional stories. Facts and reality, as we understand them, do not interest their creators – especially since their paintings almost only appear in church surroundings. It is completely bound to a specific purpose and order. Romanesque painting can be found throughout Europe. The name Romanesque comes from the round arches used in architecture and adopted by the Romans, which can be found in the architecture and painting of the time.

Gothic: Higher, Further, Freer – With Decline in Sight

(1100 – 1500)

The Gothic period, which began around 1200 A.D. and lasted until just under the middle of the 15th century (depending on the country) is characterized by two contrasts. This is one of the most famous eras of art. On the one hand, people’s thinking becomes broader and freer. A slowly awakening “I” stands against the dull conformity. Look at a Romanesque and then a Gothic church: In the Gothic one you feel crouched, but also secure.

The Gothic church will draw your gaze upwards through ever larger, light-flooded windows into a freedom you have never known before – which is scary at the same time. People have always liked to be protected (and thus be hedged).

But the new freedom corresponds with the fear of the end. In 1500, many people feared that the world would end. All this is clearly expressed in the paintings of that time. The fact that painters have ever-larger surfaces at their disposal plays a role in this, which entails an expansion of the range of themes. Gradually, more and more secular “subjects” appear in the paintings.

Technically, the discovery and two-dimensional development of the three-dimensional spatial perspective plays a major role. The perspective of meaning still changes little, but people no longer appear as inanimate objects. They are suddenly presented in a completely different way than before: the rigid and often clumsy posture of the Gothic period is replaced by a soft S-curve, which helps the bodies to move. Faces become more individual, softer, and less two-dimensional. Clothing, previously of little interest to the painter, now attracts attention and is given elaborate folds.

More and more often, secular scenes are depicted, including hunting or working in the fields. Courtly elegance moves into the center of interest. The absolute power of the church begins to fade. The cruelties of the inquisition have one of their causes in it. In the end, the church still has its partly protective, partly servant hand on everything, and yet in the late period of the era, works such as that of Breughel or Hieronymus von Bosch were created that would hardly have been suitable for the Church.

While, by the way, we hardly know any individual artists from the Romanesque period, we now find an explosively increasing number of famous names. In Italy, France, the Netherlands, Germany, and elsewhere. The first large and competing schools are emerging. Italy makes a prelude with Giotto di Bondone’s outrageous naturalism. Here, the development of panel painting is favored by the ever-larger wall surfaces away from the churches.

Renaissance: Rebirth of an “Era” That Never Existed

(1420 – 1520)

Young Hare, Albrecht Dürer [Public domain]

Around 1420 something begins that was quite logically derived from what was described above: the liberation of the individual – a kind of rebirth (hence the name). Artists of all genres, including painters, remembered their role models of Roman and above all Greek antiquity that had been buried or lost for centuries. As far as painting is concerned, this seems somewhat contradictory. Classical antiquity is mainly limited to sculpture and architecture. paintings are rather exceptions.

The Renaissance in painting is the rebirth of an art era that had never existed in its own right. But the principles of antiquity correspond very closely to those of the new movement. Portraits and all images in general, including landscapes, are becoming increasingly naturalistic and realistic. Three-dimensionality broke new ground in comparison to the purely two-dimensional representations of the Romanesque and, in part, Gothic periods.

As far as this three-dimensionality is concerned, we should exceptionally recall a sculptural work, Michelangelo’s “David”, which is one of the first sculptures of the Renaissance to be consciously conceived in such a way that you can look at it from every angle. Until then, all post-antique sculptures had been designed for viewing only from the front.

The situation is similar to the paintings of the Renaissance, although it is worth pointing out that alongside Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarotti was one of the most important pioneers as a painter (not only as a sculptor).

The Renaissance: The fresco, invented 3000 years ago, takes on a whole new meaning. Large wall surfaces enable expansive depictions of complex scenes. The painting techniques became more and more sophisticated. Faces are no longer painted in two dimensions, but in a very nuanced way, so that you have the impression that you have the person portrayed in person in front of you. Oil paints replace the tempera paints preferred until then. The Renaissance is also the starting point of the great mainly Flemish/Dutch landscape painting.

Mannerism: A Brief Period of Kitsch

(1520 – 1600)

The headline chosen here is of course meant provocatively. Not everything that has been created in the time from about 1550 – with predecessors already from 1515 – is ‘kitsch’. It seems to us today only artificial, although there are honorable reasons for this. With the newly discovered freedom of the human being goes the effort that every artist has to develop their own way of expression, their own ‘manner’.

This, however, quickly leads to exaggerations from which even Michelangelo is not entirely free, which is why some of his works are in fact no longer considered to be of the Renaissance but already of Mannerism. In Mannerist painting, the representation of feelings is deliberately exaggerated, gestures are exaggerated. Everything, including the clothing of the portrayed person, is exaggerated to the point of being impossible to do.

The slight S-curve of the Renaissance turns into an almost unnatural overturning of the body. It is not without a certain irony that it is precisely this style that becomes the first pan-European style to attract artists from all over Europe to Italy, its place of birth.

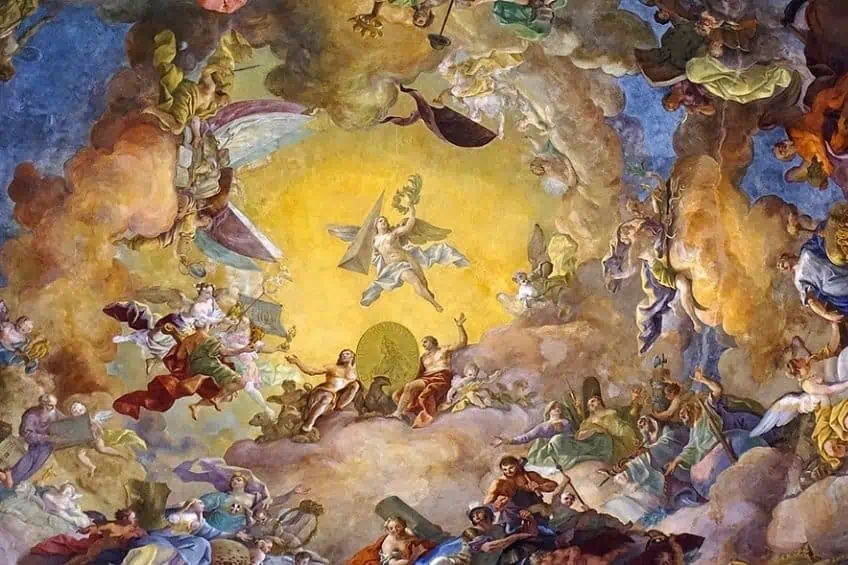

Baroque: Glorification of Power & Optical Illusions

(1590 – 1760)

Manner becomes method. Princes and prince-bishops, kings, and popes are becoming increasingly fond of seeing not the divine but their own power represented. The sceneries become more and more magnificent, up to rationally not even possible arrangements. The ‘Trompe l’oeil’, the deception of the eyes, finds its way into the painting.

More and more new academies are founded. Gold and (in sculpture) marble become the predominant materials. Bodies are depicted in full plasticity in the paintings, similar to Michelangelo’s Renaissance sculpture of David. Opposites such as those of light and shadow are emphasized beyond the natural. Above all, Baroque is the age that unabashedly displays its power in all its pomp, both in churches and castles. People are interested in displaying their fame, wealth, and power in this period.

The Rococo: A Comedy of Light, Air, and Colors

(1725 – 1780)

In the Rococo period, whose name is derived from the French word for shellwork (rocaille), and which was started there accordingly, everything that was still somehow fitted into solid forms in the Baroque period dissolved into air, light, and desire. All forms become playful. The colors become lighter up to almost transparent tones. Religious themes are receding somewhat into the background, although artists like Tiepolo left masterpieces of fresco painting in numerous churches.

The famous shepherd’s idyll, completely removed from reality, becomes ‘the’ theme of the time. As if there were no economic, social, or other constraints, everything in the Rococo period is light-hearted cheerfulness.

Classicism: Forward – Back to the Future!

(ca. 1770 – 1840)

Self-portrait Angelica Kauffman [Public domain]

Classicism was a movement that spread internationally around 1770, starting in France. Artists of all art genres, especially architecture, in addition to painting, reverted to earlier themes, techniques and forms. In many of the works created at that time, you can easily recognize the models of Greek and Roman classicism.

The colors become more two dimensional again, and even portraits become recognizably outlined again – similar to the Romanesque style. Colors recede in their meaning. The strict form sets the tone. Louis-Seize, Biedermeier, and Empire are all parts of classicism, which is often used to instill patriotic feelings in people – especially in France and Germany.

Romanticism: After Severity, a Surge of Emotion

(1790 – 1850)

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich [Public domain]

Early on, around 1795, the austere classicism was accompanied by emotional romantic aspirations, as if the cool classicism had to be countered by human warmth. The artists did not develop a holistic, tangible, and precisely definable style. The Germans tend to have a certain weight of thought, while English and especially French painters are specifically interested in the effects of light and shadow. One of the most important of them is Eugène Ferdinand Victor Delacroix.

In the paintings of the Romantic period, you will find little realism and reference to nature. In its place, sentiment and a sense of eerie beauty play a role. Many works of this period explore the subconscious and give wide scope to the depiction of feeling and danger. At the same time, pursuits like hiking and other associations were started. These wanted to discover nature, but not as it is, more as one would feel it emotionally. Everything is transfigured and elevated. The Romantics were therefore often mocked and criticized.

Realism: Reality Over Beauty

(1850 – 1925)

Promptly this movement also finds a counter-movement. Its representatives call themselves realists. That is why the style that developed at the turn of the 19th century is called realism. In order to stop the exuberant Romantics, realism aims to show nature, people, animals, and everything that can be represented as it really is. Gustave Courbet speaks of the “obligation of art into truth”.

The realists see not only the beautiful and the good, but also the evil and the ugly, and they show this too in an unembellished way. The play of light and shadow is also cultivated in realism. Nevertheless, the paintings of this time are seldom particularly homely or likable – realistic, that is. Critics have complained that even erotic scenes in the paintings of realism lack exactly that: eroticism. No wonder that this period is also criticized, sometimes severely. Schiller calls realism “mean”. Goethe says that art must be ideal, but not realistic.

Impressionism: The Old World Ends, a New One Begins

(1850 – 1895)

The Flower Terraces in the Wannsee Garden to the Southwest, Max Liebermann [Public domain]

Impressionism began in the second half of the 19th century. It is often attested to have finally brought an end to classical music and heralded a completely new world – the modern age. One of the things that are fundamentally different in this art style: painting is now done outdoors, whereas previously outside was only sketched and the actual paintings were created exclusively in the studio. Outside, “en-plein-air”, the artists have completely different possibilities than before to catch even rapidly changing light reflections and to capture them in the painting. “Impression – Sunrise” by Claude Monet is regarded as the very first impressionist work ever.

The name Impressionism was initially a swearword because critics thought that these painters did not paint, but rather smeared. In fact, the brushstroke sometimes becomes furiously wild and can no longer be compared with the painting of past art periods. Shapes and lines fade into the background. The pure color takes the lead.

Completely new colors are put together from individual dots of color (especially in the impressionistic variety of pointillism). Painted objects can often only be recognized from a slightly greater distance than what they represent. The artists also no longer want to lecture, but to paint for the sake of pure painting (l’art-pour-l’art). The large galleries, often doing international exhibitions, are gaining in importance.

Symbolism: Bitter Enjoyment of Sin, Death, and Passion

(1890 – 1920)

Between 1880 and 1910 people created the most important works of Symbolism. This style (which we prefer to speak of as a period) also has its origins in France. Compared to factual perception, the depiction of thoughts and feelings occupies a large space, but unlike in Expressionism or Impressionism, for which it is considered the link.

At the same time, with its mostly clear forms, it anticipates Art Nouveau. Sickness, sin, death, and passion are, with a certain decadence, among the preferred themes of Symbolism.

Art Nouveau: A Kiss Travels Around the World

(1890 – 1910)

“The Kiss” by Gustav Klimt is not necessarily the most important pictorial work of Art Nouveau, but certainly one of the most famous worldwide. Large floral elements and soft, curved lines characterize this style – which is known in many countries as the Secession style.

Symmetry plays an increasingly minor role. Swing and playfulness, even a certain youthfulness, find their way into the painting. Art Nouveau attempts to bring nature into the cities. Apart from the purely decorative aspects, which are often held against it, Art Nouveau has serious political content.

Expressionism: Painting as Social Criticism

(1890 – 1914)

The Yellow Cow, Franz Marc [Public domain]

Expressionism from the end of the 19th century onwards takes a targeted stand against naturalism. The painters of this movement had little interest in showing the outside of things. They are interested in the expression of their own feelings. You find a certain aggressiveness in these paintings, something wild and archaic.

Expressionism, which originated in Germany, is contrasted with French Fauvism, which, like the latter, is expressly conceived as a contrast to Impressionism. Around the time of the First World War, artists produced works of often disturbing intensity. A clear criticism of power and society was spreading in painting. It finally becomes highly political.

Cubism: Piecing the World Back Together!

(1906 – 1914)

Juan Gris [CC0]

From 1906 onwards, painters from France went over to dismantling. Without having anything like a concrete program, artists like Pablo Picasso literally took the world as it presented itself to them and reassembled it in a different way according to their own preferences. A thing or a person is no longer shown in a unified view but broken down into individual parts, initially occasionally referred to by viewers as cubes (French “cube” = cube), which are intended to show the object simultaneously from different sides.

The cubists no longer recognize rules of any kind. Not a program, but a powerful influence: Cubism has had a major impact on all subsequent art styles of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Futurism: Classical and Hostile to the Body

(1909 – 1945)

Futurism is the first art movement “founded” by an individual with a solid program. The Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote a “futurist manifesto” in which he rejected Christian morality and rejected any social references. However, Marinetti himself is not a painter. Nevertheless, painting became the most important art form of Futurism. The Futurists opposed the models of the Classical period, and they proved to be extremely hostile to the body.

They rejected nude painting as depressing and repulsive. Everything that has been handed down is suspect. Remember a German buffoon saying, “Is this art, or can this go away?” That’s pretty close to futuristic thinking. Futurists are also accused of being too close to fascism.

Dadaism: Nonsense as the True Meaning of Things

(1912 – 1920)

There are several theories about the origin of the name “Dada”. One of them is that the writer Hugo Ball, as a joke, poked around in a German-French dictionary and came across the word “dada”. “Dada” means “hobbyhorse” in the French children’s language. Dada is based on provocation and illogic, and sees itself among other things as an anti-war movement, even during the First World War.

Existing values and rules are questioned and overcome by nonsense. Objects of everyday life are suddenly works of art. Dadaism is characterized, among other things, by the fact that it unites various types of art – including poetry and dance, in one work of art. With its “nonsensical” character it breaks many taboos, and at the same time brings about numerous technical innovations and has had a significant influence on subsequent art movements to this day. Since Dada, painting has been more than a reflection of reality. Dada is an early form of action art.

Surrealism: Everything Real is Really Unreal

(1920 – 1930)

It would be unusual if you did not know Salvador Dalí’s painting “The soft watches”. Dalí is one of the most important of the surrealists – perhaps the most important. Initially, this kind of art was despised by the public. Today, its products are even anchored in the minds of conservative viewers. The surrealists only deal with reality in so far as they merge it with their own dream world.

As time passes, the clocks they were supposed to be representing can also melt away. In contrast to the satirical style of Dadaism, Surrealism is psychoanalytical and deals with the fantastic and the unconscious. Surrealism turns against the encrusted thought structures of the bourgeoisie.

The New Objectivity: Focus on Pure Functionality

(1925 – 1965)

Already after the First World War, a turn to visible things sets in, while the Surrealists begin to counteract these exact things. Similar to the Expressionists, the representatives of New Objectivity increasingly took up socially critical themes. The chaotic events of the war resulted in a longing for order and tradition, which is expressed in New Objectivity. Images of New Objectivity often appear unemotional, sober, and very technical.

Many technical innovations from the light bulb to the radio are now themes in paintings. Like all modern art movements, this one is not homogeneous but splits up into several different “wings”.

Abstract Expressionism: Art Emigrates

(1948 – 1962)

For the first time, an art movement is emerging not in Europe but in North America – particularly in the USA. From around 1940 onwards, action painting and color field painting attracted attention there, which seems to have finally overcome the representational. Paint is poured in buckets onto the ground, which does not always have to be a canvas. It is “painted” with the fingers instead of with a brush or spatula.

The paint application can become so thick that the finished “painting” takes on a completely unique form. From America, the movement, whose most important representatives are probably Jackson Pollock and Marc Tobey, spread to Europe. In the past, it had always been the other way around. From the conservative political side, it is branded as “un-American” during the Cold War. There is no stopping it.

Pop-Art: Everything is Art – Art is Everything

(1955 – 1969)

For the artists of Pop Art, which is once again being created in the USA and at the same time in England, everything is final and everything is art. Advertising signs, comics, trivial things of everyday consumption up to the tin can are suddenly objects of artistic contemplation.

Clear contours and uniform color surfaces dominate. Serial prints and photorealism find their way into painting and graphic art. David Hockney is still considered one of the most important representatives of English Pop Art, although he only painted a few paintings of this art movement and soon turned to other forms of expression.

Modern Art in the Art Movement Timeline

Neo-Expressionism

(1980 – 1989)

From the 1980s onwards, a movement of painters emerged who created life-affirming, representational and large-format paintings. Their designs were mainly the big city or big-city life. The period, or art movement, got its name from the Fauves of Fauvism.

The hotspot for the new movement was Berlin, but around 1989 the artists dispersed, some continued to paint this style in New York.

Understanding the art periods timeline is necessary for anyone wanting to really understand the importance of different artworks. The different art eras have each brought something new to the world and helped to inspire the next generation of painters. We hope that this look into the different periods of art has helped to enlighten you on the famous artworks throughout time.